New Zealand's Relations with the US and China: A Survey of the NZ Strategic Studies Community

Twitter: @ReubenSteff

Abstract: This article contains research from a written survey conducted in late 2016 of members of the New Zealand strategic studies community. They were asked to assess the state of relations between NZ, the US and China at that time, the expected future state of relations, and give their views on various aspects of the three states bilateral and triangular relations. The findings predict greater turbulence between Beijing and Washington over the coming decade and make recommendations for policymakers in NZ to consider. This article outlines these findings, provides brief commentary and suggests areas where subsequent research could prove fruitful.

The first part of this article contains the quantitative survey findings, followed by some of the qualitative responses with brief commentary from the authors. The full set of qualitative responses is included at the end of the article in an appendix. We invite readers to consider these to draw their own conclusions and to use them for their own research purposes. The names of respondents to the survey have been kept anonymous. The authors of this article can be reached via email: rsteff@waikato.ac.nz and fjd5@students.waikato.ac.nz.

NZ-China: Good Relations

Question 8 asked if NZ’s increasingly close economic relationship with China is undermining or affecting its relations with the US.

A large majority, 95%, believed that it is not. One respondent said: ‘No, if it’s purely economic interests and relations. Yes, when this becomes part of Washington’s overall calculation of NZ’s value in US strategic relations with China’. Another said: ‘No. Some Washington commentators claim NZ is misty-eyed over the economic relationship but no signs this is the ‘official’ approach. There is good understanding in Washington of the reasons why NZ and many other US friends and allies have formed close economic ties with China.’ Another stated, ‘The US seems to understand and respect that as an exporting nation, NZ will have close economic ties with China… The US seems to regard NZ as a trusted partner in Asia, who can be relied upon to convey messages to China, despite the economic relationship.’

Discussion

The above comments should provide some reassurance for NZ policymakers as we can deduce that, in the eyes of the members of the NZ strategic studies community that took part in the survey, NZ’s expanding trade relationship with China has not played a role in undermining NZ-US relations (a survey of American officials and experts would be required to ascertain whether this view is mirrored in the US). However, as one respondent wrote, there is a potential that Washington could negatively view NZ trade relations with China in terms of the ‘overall calculation of NZ’s value in US strategic relations with China’. This statement is worthy of further reflection and suggests that, arguably, if Chinese-US relations were to deteriorate Washington could come to view its Asia-Pacific allies, including NZ’s, trading relationships with China as a factor that delivers relative gains to Beijing at the expense of Washington, leading Washington to encourage its allies reduce trade with Beijing.

Bio:

Reuben Steff is a lecturer of International Relations and Global Security at the University of Waikato in the Political Science and Public Policy Programme. His expertise and research interests lie in great power competition, with a focus on the intersection between nuclear deterrence and missile defence, the emerging technological aspects of the arms race, small states and New Zealand foreign policy. His latest co-authored book is “Dr Reuben Steff & Dr Nicholas Khoo, Security at a Price: The International Politics of US Ballistic Missile Defense (Rowman & Littlefield, November 2017).”

Francesca Dodd-Parr is a PhD student at the University of Waikato. She is currently working on research into decision-making in the housing policy space at a local government level. She is also interested in international relations, geopolitics and NZ national security. Her PhD is part of National Science Challenge 11, Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities for New Zealand.

Abstract: This article contains research from a written survey conducted in late 2016 of members of the New Zealand strategic studies community. They were asked to assess the state of relations between NZ, the US and China at that time, the expected future state of relations, and give their views on various aspects of the three states bilateral and triangular relations. The findings predict greater turbulence between Beijing and Washington over the coming decade and make recommendations for policymakers in NZ to consider. This article outlines these findings, provides brief commentary and suggests areas where subsequent research could prove fruitful.

The first part of this article contains the quantitative survey findings, followed by some of the qualitative responses with brief commentary from the authors. The full set of qualitative responses is included at the end of the article in an appendix. We invite readers to consider these to draw their own conclusions and to use them for their own research purposes. The names of respondents to the survey have been kept anonymous. The authors of this article can be reached via email: rsteff@waikato.ac.nz and fjd5@students.waikato.ac.nz.

Introduction

While in recent

decades New Zealand’s (NZ) key security relationships have remain centered on its

traditional partners (Australia, the U.S., and U.K.) and have, in some

instances (such as NZ-US security relations) deepened over the past decade,

China has become one of Wellington’s key trading partners. This raises a potential dilemma for

NZ policymakers, as China is a non-traditional partner, does not

share many of its values and is engaged in a competition for influence across

the Asia-Pacific with the United States. The crux is that China’s growing economic

(and military) power offer Beijing immense influence to promote policies that

support its interests and that it could leverage against states in the

Asia-Pacific, such as NZ, to adopt positions at the expense of American

interests. Naturally, the US could also encourage and/or pressure its regional

allies to take positions that are at odds with Chinese interests.

To examine the issue of NZ’s ties

with the US and China, and potential complications that could arise from the interrelationship

between Wellington’s two sets of bilateral relations with either power, the

authors of this article conducted a written

survey of the NZ strategic studies community in late 2016. Separately, they also penned a

journal article that examines and contributes to the existing scholarly

literature on this issue and that complements this article.[1] The survey involved contacting members

in academia, the think tank community and former government employees with

expertise on NZ foreign policy. In total, 48 candidates were approached, with

18 (40%) choosing to take part in the survey. To ensure their responses were

free and frank we stipulated that their identities would remain anonymous. We can say, though, that the grouping

includes individuals with policy experience from their time in government, individuals from NZ think tanks and academia, and many of the participants continue to actively contribute to discussions and debates on NZ foreign

policy in academia and civil society.

The final survey product contained a

set of quantitative questions, some of which also allowed survey participants

to add a qualitative response, and a second set of questions that were solely

qualitative. The rationale behind the survey was that expert views of the state, and

expected future state of relations between NZ and the US and China, and

identification of pressing issues, could spur debate, inform policymaking, and

allow strategic anticipation and adjustments to take place based upon future

expectations.

In retrospect, some of the questions were slightly ambiguous but we also reasoned that, in some instances, respondents should

have some leeway to interpret the question as they saw fit. Furthermore, qualitative questions allowed participants to

expand and elucidate what lay behind their thinking. In many cases, questions

were direct and not ambiguous.

Given it is now

2018, we feel it is worth speculating that had the survey been conducted in the

wake of the (largely unexpected) victory of Donald J. Trump in the US election,

respondents may have been more skeptical about their assessment of

the future state of US-China ties and perhaps US-NZ ties as well than they

were when the survey was taken in late 2016 (immediately prior to the US

election). However, we do not believe that this renders the findings of the survey redundant as broad trends across the Asia-Pacific are likely to continue to

play out irrespective of who sits in the White House. Ultimately, this survey should be

viewed a ‘snapshot in time’ and we hope that scholars and policymakers may find

some value in it irrespective of when it took place.

The next section outlines the views

of the NZ strategic studies community as they relate to NZ’s relations with the

US and China.

The Survey’s Findings

Assessing the Shape of Bilateral Relations

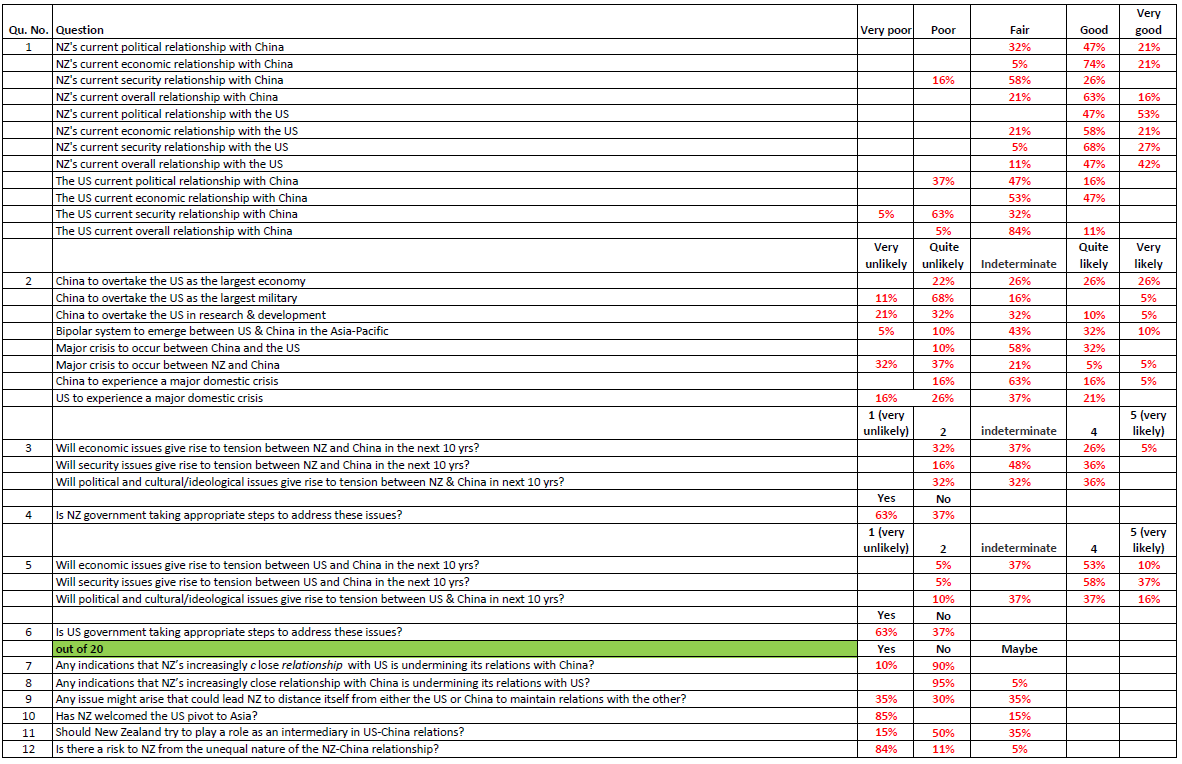

The first set of quantitative

questions required

participants to rate NZ-US, NZ-China and US-China relations along a 1-5 scale,

with 1 being ‘very poor’, 3 ‘fair’, and 5 ‘very good’. The findings

from the survey are contained in the table below. The rest of the section

discusses the findings and draws upon the qualitative responses to highlight

some of the notable points raised by the respondents. Readers should bear in

mind that the word ‘current’ in the table below refers to late 2016, before Donald

J. Trump won the US election.

Table 1: Survey Findings (late 2016)

NZ-China: Good Relations

A majority of survey participants,

68%, felt that NZ had ‘good/very good’ political relations with China,

and a large majority of 95% recorded that NZ had ‘good/very good’ economic

relations with Beijing. NZ’s current security relationship with China

was not judged positively, with 16% rating it ‘poor’, 58% rating it ‘fair’ and 26% ‘good’.

More than

three quarters of respondents, 79%, believed NZ's overall relationship

with China was ‘good’ or ‘very good’. In other words, NZ-China

relations were generally viewed positively, with a majority of responses

falling into the ‘good’ category across each question.

NZ-US: Good-Very Good Relations

A majority of survey respondents

judged NZ-US relations more positively than they did NZ-China relations. 100%

of participants rated NZ’s political relations with the US ‘good/very good’, 95%

felt NZ-US security relations were ‘good/very good’ and just 5% felt

they were ‘fair’. 79% participants judged the economic

relationship to be ‘good/very good’, with 21% judging this aspect ‘fair’. Notably, 89% agreed that NZ's overall

relationship with the US was ‘good’ or ‘very good’, a figure 10% higher than

NZ-China relations.

US-China:

Fair Relations

Unsurprisingly, participants did not

rate US-China relations nearly as high as they did NZ-US or NZ-China relations.

The US-China political relationship leaned towards negative territory,

with 37% judging it ‘poor’, 47% ‘fair’, and only 16% rating it ‘good’. No

respondents placed it in the ‘very good’ category. The economic relationship

received a more positive response, with 53% of respondents rating it ‘fair’ and 47% rating it ‘good’. The security

relationship, however, was judged negatively, with 68% of respondents

rating it ‘very poor/poor’, with 32% ranking it ‘fair’. No respondent rated it ‘good’ or ‘very good’. A large majority, 84%,

judged the overall US-China relationship to be ‘fair’.

Discussion

The findings above are not particularly surprising. For example, considering NZ’s trade with China has

grown markedly in recent years, we would expect this to be rated the most

positive area of NZ-China ties, and political relations to also receive a high mark.

Yet, while the political relationship between Wellington and Beijing is robust,

and some security links are being developed, they are clearly not as deep or

broad as NZ-US relations. The findings are also consistent with the concern

that, owing to its diverging economic and security relationships, and relative

position of weakness vis-à-vis the US and China, Wellington could face future

policy dilemmas. In particular, the responses we obtained regarding US-China

relations, especially in the security sphere, where 68% placed it in the

‘poor/very poor’ category, should be cause for some concern in NZ policymaking

circles.

Respondent predictions

The second set of questions asked

respondents to provide an assessment as to whether they believed certain

developments would take place in the next 10 years. A scale of 1-5 was used,

with 1 being ‘very unlikely’, 3 ‘indeterminate’ and 5 ‘very likely’. Over half of

the participants believe it ‘quite likely/very likely’ China will overtake

the US as the largest economy in ten years, 26% judged it ‘indeterminate’, and 22% stated it was ‘quite

unlikely’. Regarding the likelihood of China overtaking the US as the

largest military power a large majority, 79%, judged it ‘very

unlikely/quite unlikely’, 16% ‘indeterminate’ and 5% rated it ‘very likely’.

Regarding the likelihood that a ‘bipolar

system’ will emerge in the Asia-Pacific,

respondents leaned towards the affirmative, with 42% reporting this ‘quite

likely/very likely’, 43% ‘indeterminate’ and 10% ‘quite unlikely’, and 5%

‘very unlikely.’ On the likelihood of a major

crisis occurring between China and the US,

58% marked ‘indeterminate’, 10% ‘quite

unlikely’ and 32% thought it ‘quite likely’. On the likelihood of a major

crisis occurring between NZ and China, 69% judged this ‘very unlikely/quite

unlikely’, 21% ‘indeterminate’, 5% ‘quite

likely’, and 5% ‘very likely’.

Discussion

Most commentators believe China’s

economy will overtake the US’s in the next ten years. On the one hand, a larger

and more prosperous economy should result in increased demand for NZ’s dairy

products and generate additional tourism for NZ. On the other hand, as China’s

economy grows it will translate into greater Chinese influence throughout the

Asia-Pacific region, buttressed by growing military capabilities. This will

further alter the status quo and has the potential to create a more contentious

bipolar Asia-Pacific region.

Respondents did not believe China’s

military would be larger than that of the US in ten years. This may reflect the fact that it takes time for economic power to translate into new military

might. In a sense then, if NZ’s close security relationship

with the US is thought of as a ‘bet’ on who will be the predominant

military power in the Asia-Pacific over the next ten years, then if this

prediction holds true NZ decision makers have made the right choice for the

time being.

More than half of respondents

reported that the likelihood of a major US-China crisis occurring over the next

ten years was ‘indeterminate’, but one third believed it to be

‘quite likely’. This should not be a reassuring finding for NZ policymakers, as

a major US-China crisis is the most likely reason that could lead NZ to be

forced to ‘pick sides’ or adopt policies that threaten its relations with one

or other state. NZ’s foreign policy ‘independence’ could be tested. On a

positive note, 69% of respondents judge the likelihood of a major crisis

occurring in NZ-China relations to be ‘very unlikely/quite unlikely’.

NZ-China: Potential sources of

tension (economic, security, ideological/political)

The next set of questions asked

whether the following three issues, economic, security,

political/ideological, would give rise to tensions between NZ and China

in the next 10 years. Responses were evenly distributed between 2 (‘quite

unlikely’), 3 (‘indeterminate’) and 4 (‘quite likely’) on each

count, with only one respondent rating economic issues ‘very likely’ to cause

tensions. A related question asked whether participants thought the NZ

government was taking appropriate steps to address these issues. A majority,

63% reported ‘yes’ and 37% ‘no’. Qualitative responses elucidating participants thinking on this question are included in the appendix.

US-China: Potential sources of

tension (economic, security, ideological/political)

Five percent of respondents believed

the chances of economic issues generating tension in the US-China

relationship in the next ten years was ‘quite unlikely’, 37% ‘indeterminate’ and 57% ‘quite likely/very likely’.

When it came to security issues, an overwhelming majority, 95%,

believed it was ‘quite likely/very likely’ to cause tension. On the issue of

whether cultural/ideological issues would generate tension, 53% felt it

was ‘quite likely/very likely’, 37% ‘indeterminate’ and 10% ‘quite unlikely’. Across

all three sets of issues a majority of respondents leaned towards there being a

greater chance of tension occurring than not, with security issues being the

most likely source. A related question asked whether

participants believed the US government was taking appropriate steps to address

these issues, with a majority of 63% reporting ‘yes’ and 37% ‘no’. Qualitative responses to this

question are addressed below.

Discussion

Of the respondents that said the US

government was taking appropriate steps, a number mentioned the value of

security and economic initiatives established between the US and China, or what

one called a ‘super structure of dialogue tracks’. This showed that both sides

are ‘aware of differences but adapt to them and contains them within the policy

that officially identifies China as a partner, not a rival or enemy.’ Many

qualified their answers. One participant said ‘Yes but Washington acts with a

realist mindset that may serve to heighten tensions’. Another believed

‘ultimately, appropriate adjustments would require the US to cede influence and

accept China as an equal player in the economic and security spheres, which

does not sit well with the US view of its global role’. Another stated that on

security issues the US ‘should try and seek an agreement on the mutual

accommodation of currently defined needs in the South China Sea, and give fresh

consideration to joint initiatives on Korea and even possibly Taiwan.’

Six respondents noted that there were

domestic issues in the US and China that could complicate the relationship.

This included three respondents suggesting that a Trump presidency would

jeopardise US-China relations; two respondents noting there is evidence of

internal differences between hardliners and doves across the US system,

resulting in internal disagreement over how robust the US response to China

should be. Finally, one respondent believed ‘growing nationalistic sentiment

within China’ could be a ‘barrier to managing the inevitable tension in the

US-China bilateral relationship.’

Question 7 asked respondents if there

were any indications that NZ’s increasingly close

security/military relationship with the US is undermining or affecting its

relations with China in any way.

A large majority, 90%, did not

believe it was, with 10% saying ‘not yet’. Four respondents noted that China

would be closely watching NZs messaging and positioning on issues of importance

to China, such as the South China Seas. A respondent that captured both these

points stated, ‘It was notable that China effectively fired a warning shot

across the bows when it complained about NZ’s recent participation in an FPDA

exercise in the South China Sea… Whilst NZ and most other regional states do

not want to have to choose between China and the US, China may put pressure on

them to choose Beijing over Washington.’ Other respondents suggested that NZ’s

careful positioning and wording, for example not naming China in its response

to the Arbitral Tribunal’s ruling (in October 2015) against Beijing and in favour of the Philippines on the South China Seas

dispute, supports NZ’s independent foreign policy. This reduces China’s

perception that NZ poses a threat. On this latter point, one respondent stated

approvingly that ‘NZ tries hard to appear as independent as possible, with a

‘no surprises’ policy in order to re-assure China of its intentions’.

A large majority, 95%, believed that it is not. One respondent said: ‘No, if it’s purely economic interests and relations. Yes, when this becomes part of Washington’s overall calculation of NZ’s value in US strategic relations with China’. Another said: ‘No. Some Washington commentators claim NZ is misty-eyed over the economic relationship but no signs this is the ‘official’ approach. There is good understanding in Washington of the reasons why NZ and many other US friends and allies have formed close economic ties with China.’ Another stated, ‘The US seems to understand and respect that as an exporting nation, NZ will have close economic ties with China… The US seems to regard NZ as a trusted partner in Asia, who can be relied upon to convey messages to China, despite the economic relationship.’

Discussion

The above comments should provide some reassurance for NZ policymakers as we can deduce that, in the eyes of the members of the NZ strategic studies community that took part in the survey, NZ’s expanding trade relationship with China has not played a role in undermining NZ-US relations (a survey of American officials and experts would be required to ascertain whether this view is mirrored in the US). However, as one respondent wrote, there is a potential that Washington could negatively view NZ trade relations with China in terms of the ‘overall calculation of NZ’s value in US strategic relations with China’. This statement is worthy of further reflection and suggests that, arguably, if Chinese-US relations were to deteriorate Washington could come to view its Asia-Pacific allies, including NZ’s, trading relationships with China as a factor that delivers relative gains to Beijing at the expense of Washington, leading Washington to encourage its allies reduce trade with Beijing.

Question 9 asked respondents if they ‘see

any issue(s) that are arising, or might arise, in the next 10 years that could

lead NZ to distance itself from either the US or China to maintain its

relationship with the other?’

In response, 35%

reported that they believed there was an issue that would arise, 30% reported ‘no’, and 35% stated ‘maybe’. This

suggests that respondents lean by a slight margin towards ‘yes’ rather than ‘no’. Most qualitative responses

suggested that NZ found itself attempting a precarious balancing act to retain

positive relations with both in order to hedge against uncertainty, but that

this position was fragile, as ‘any shifts in the international strategic

environment will make such hedging difficult.’ Another said ‘Yes. It is not

improbable that should Sino-US relationships deteriorate, that there will be

implicit and explicit pressures for NZ to take sides.’ One participant said

‘Managing relations with the two large powers will be the single biggest

challenge for NZ diplomatic tradecraft in the next decade and beyond. There is

no obvious issue existing or likely to emerge in the medium term that would

compel NZ to ‘make a choice’.’ The South China Seas was identified

as a key issue.

Question 10 asked survey participants

if ‘NZ welcomed the (Obama administration’s)

‘pivot to

Asia?’

A majority, 85%, believed that NZ

welcomed the policy. The consensus was that America’s presence in the region

was a ‘stabilising force’ and helped to ‘balance’ the growth of Chinese influence.

One respondent said, ‘Quietly, yes, but avoided

emphasising it. Many NZers are sceptical of it and of the US, so the NZG find

no political capital in publicising it. The US warming is welcome because it

validates NZ policy and assists the NZDF, that is, it serves NZ interests. But

NZ has no wish to exacerbate US-PRC tensions by overtly taking one side or the

other. So policy is an artful and pragmatic muddle.’ Another participant said

NZ’s support for the policy came, in part, because Wellington did not view the

pivot as a containment strategy vis-à-vis China.

Question 11 asked whether ‘NZ

should try to play a role as an intermediary in US-China relations?’

50% responded ‘no’, 35% ‘maybe’

and 15% ‘yes’. Respondents who marked no were

very strident in their position, with typical responses including: ‘Absolutely

not – the concept of NZ as an ‘honest broker’ is the product of delusions of

grandeur.’ Another said, ‘Absolutely not: it is likely to get crushed! Not only

would trying to play such a role almost certainly be unsuccessful, it would most

likely cause difficulties in NZ’s relations with both countries.’ Those who

indicated ‘maybe’ suggested there could be value in this for NZ but only if

Beijing and Washington were to welcome it. Two of the three respondents who

said ‘yes’

elaborated, with one stating: ‘NZ can certainly play a constructive role

between the two countries. In the process we can potentially have an outsize

influence on both, although we need to walk a very fine line and choose our

battles carefully to avoid being caught in the middle or being on the wrong

side of issues.’ The other wrote, ‘Yes. NZ has

excellent relations and, in that sense, is quite different from Australia.’

Question 12 asked if there ‘Is a

risk to NZ from the unequal nature of the NZ-China relationship?

In response, 84% said ‘yes’,

11% ‘no’ and 5% ‘maybe’.

Most

respondents who marked yes, noted that China could use its

economic leverage against NZ (and the region). For example, ‘China

has shown itself quite ready to use its political influence to secure its economic

goals, and vice versa. There is no reason to suppose NZ will be exempt from

this.’ Another stated: ‘Yes. NZ will effectively be forced to accept things

which are not necessarily in its own national interests.’ To some, this in turn

requires American power to balance China, ‘Yes,

the asymmetry of power in the relationship is a reality and a risk. We cannot

wish it away. But there are ways to ‘manage’ the situation. NZ should do its

best to support an active role for the US in the region. If the US is not

actively serving as a balancer to Chinese power, China will seek to maximise

its influence over small and medium size states. This has been the historical

experience of the region when China was strong.’

Question 13 asked, ‘Should NZ take

a public stance on territorial/sovereignty disputes between China and its

neighbours over the South and East China Seas?’

A majority, 61%, responded ‘yes’ while 39% said ‘no’. Those in the affirmative suggested

NZ had to take public stances in favour of international law to ensure large

powers abided by the rules-based international system. Those who responded no

believe the NZ government’s decision not to take overt sides was an appropriate

one. Interestingly, a majority of both groups said it was important that NZ did

not identify specific rule breakers, with one respondent believing that

criticising China’s behaviour would not have clear benefits for NZ. One

respondent, however, disagreed with this view, stating that NZ should not just

ask others to ‘respect international law, but to actually adhere to it. NZ

cannot say it supports a rules-based international system and then fail to

condemn states, which flout the rules.’

A final question asked, ‘Is

there anything else you would like to add regarding NZ’s relationship with the

United States, and the potential national security implications for NZ of this

triangle?’

Notable responses included that while

non-government personnel might like more decisiveness from the NZ government,

‘in favour of the US and its democratic neo-liberal ideals, a nuanced

examination reveals the wisdom of its current understated and ill-defined

policies. Large majorities of the NZ public are sceptical of the US (and even

more are sceptical of China) so keeping control of the policy narrative by

avoiding energising these minorities is prudent NZG policy.’ One respondent saw

some opportunity in the emerging situation, stating ‘there are opportunities

stemming from the greater attention and consideration we get from two major

powers both seeking to build influence in our region’. Another said that NZ’s ‘strategic

dilemma’ should be

viewed in a wider context, ‘When issues of international law emerge within ARF

or EAS this is not just a situation of the US v China. Most of Asia (Australia,

Japan and much of ASEAN) also look closely at our statements. There is also the

principle that NZ regards as critical, which is the importance of international

laws and norms – as a small state it is integral to our foreign policy

independence. So issues like the South China Seas are not simply about which

large power we are ‘siding with’. The stakes are far higher than that. In the end, and NZ’s official statements to

date deal with this, it is about thinking carefully about both values and in

fact the majority of our global connections (including notably Australia, our

most important relationship).’ Another response also recommended viewing

NZ-US-China relations in regional terms stating, ‘In terms of national

security, the main threat to NZ from the US-China relationship seems to come

from a destabilisation of the wider region, rather than from a direct threat to

NZ’s territorial integrity or political sovereignty’.

One response was at odds with the

oft-stated position that NZ can successfully steer a middle path between

Beijing and Washington, ‘Trying to maintain an equidistant relationship with

the PRC and US when NZ is trade dependent on the PRC and security dependent on

the US is akin to straddling a barbed wire fence while standing on ice blocks.

The strategic competition between the US and PRC in the Asia-Pacific region is

the ice that undermines the balancing act and at some point a hard choice will

have to be made to go one way or the other.’

Final Comments and Future Research

We believe a key finding is that most

survey respondents foresee a decline in US-China relations over the next 10

years. It’s possible that this

response would have leaned even more heavily towards negative territory had the

survey been undertaken after the 2016 US election. In particular, as Table 1

shows, 1/3rd of respondents believe a ‘major

crisis’ is likely to occur between the US and China. Given the stakes involved, NZ policymakers would do well to view

this with some concern. Furthermore, if tensions rise we should anticipate that

influence and pressure from Beijing and Washington could be brought to bear on

regional states, even small ones like NZ, to make decisions they would prefer

to avoid. How NZ calibrates its foreign policy with this in mind will be

essential to NZ’s continued prosperity.

As a result of the survey’s findings,

we believe there is significant scope for future research on many of the issues

it raises. For example, how does Australia interrelate with NZ’s triangular

relations? How are other small states in the region managing their divergent

relations with Washington and Beijing? Can best practice insights between small

states be shared? Is it possible that NZ’s economic ‘reliance’ on the Chinese market, and

thus the potential influence this affords China over NZ, is less than it is

sometimes claimed? And what steps to diversify away from the Chinese could be

taken? (and is this actually desirable if we believe forecasts that China’s

power will continue to rise?) There may also be value in Wellington conducting,

in collaboration with academics, scenario planning for a range of

contingencies. How would Wellington respond over an immediate crisis in the

South China Seas where Washington or Beijing were requesting Wellington support

for their respective positions? What position would NZ take if China were to make a rapid

bid for regional hegemony? What if the US sought to

pre-empt China’s continued rise by, say, forming a new Asia-Pacific alliance à

la NATO, inviting NZ to be a member, or attempting a naval blockade of the

Chinese mainland? After all, since WWII, US grand strategy has consistently

sought to prevent the emergence of regional hegemons and forms of pre-emption may come to be viewed as a ‘rational’ option for a unipolar power that

fears its position is slipping away. What would Wellington do in these

situations? Is there value in considering the pros, cons, and mechanisms

through which NZ could entertain alternative versions of strategic alignment?

Does NZ have an effective ‘strategic foresight’ capability built into its

government apparatus and can it be harnessed in a way that provides insight

into how NZ could best be positioning itself today with the issues this paper

has in mind?

While this article does not offer answers to the potential issues and complications inherent in NZ's place between the US and China, we hope the survey findings and issues they raise spur debate and reflection over what could become the greatest foreign policy challenge to NZ and many other small states in the Asia-Pacific this century.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge

respondents from the NZ strategic studies community that took the time to

participate in the survey.

Reuben Steff is a lecturer of International Relations and Global Security at the University of Waikato in the Political Science and Public Policy Programme. His expertise and research interests lie in great power competition, with a focus on the intersection between nuclear deterrence and missile defence, the emerging technological aspects of the arms race, small states and New Zealand foreign policy. His latest co-authored book is “Dr Reuben Steff & Dr Nicholas Khoo, Security at a Price: The International Politics of US Ballistic Missile Defense (Rowman & Littlefield, November 2017).”

Francesca Dodd-Parr is a PhD student at the University of Waikato. She is currently working on research into decision-making in the housing policy space at a local government level. She is also interested in international relations, geopolitics and NZ national security. Her PhD is part of National Science Challenge 11, Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities for New Zealand.

Appendix: Full Survey Responses (qualitative)

1.

Do you believe the New Zealand

Government is taking appropriate steps to address sources of tension (economic, security, ideological/political) between

NZ and China?

·

Yes. The NZG is (and has been for

decades) aware of its political, security, and economic differences with China

but is committed to managing them within the overall framework of pursuit of

mutual benefit so far with success. I

foresee few circumstances that would alter this save a ‘black swan’ event.

·

No, it is being responsive rather than taking the initiative in addressing likely causes of tension in

the future.

·

The New Zealand government may be

aware of the issues, and it could be more pro-active in coming up with

responses, rather than ad-hoc.

·

Yes.

·

Specific issues where differences

arise are being well managed, without risk to the broad relationship important

to both parties.

·

Yes. But it is difficult to

speculate on future scenarios. Probably

the test case is positioning prior to the Philippines arbitration case. Minister McCully’s statements refer.

·

As a small state we also need to

consider how best to approach the China relationship. The tools for New Zealand are largely multilateral

institutions, bilateral channels and public statements. We have to consider which is the most

effective and influential combination on a case by case basis.

·

I am generally quite supportive of

the Key government’s China policy, with one conspicuous exception, which I

shall expand on here. This concerns Chinese ownership of New Zealand New

Zealand private and commercial assets. The current New Zealand government needs

to establish a clearer and more robust legislation to address this issue. For

example, my view is that there is understandable frustration on the part of New

Zealanders seeking to enter the housing marker, at the extent of the influx of

Chinese (and other foreign nationals) purchases of housing in the Auckland

region. This ‘problem’ has already extended to other parts of New Zealand. To

be absolutely clear, while this is a complex issue, my view is that this is

basically an internally generated problem, caused in no small part by lack of

robust legislation by the Key government and the governments that preceeded it.

In making real estate related investments in New Zealand, Chinese (and other

non-New Zealand) nationals are simply acting in ways that are perfectly legal

and rational. Therefore, why is the current government not adopting a more

proactive approach on such an important matter? I’m puzzled by the degree of

inertia displayed on such a critical aspect of New Zealand domestic policy that

has clear potential to spiral into the foreign policy arena, affecting

relations with China. After all, governments in Asia routinely use legislation

to prevent the politicisation of housing issues. It is well past time for the

Key government to act, in the interests of New Zealand, and other states (not

least China) whose citizens are interested in investing in New Zealand.

·

No need to do more.

·

Probably not – there issues are

relatively new and understandable preference during good economic times is to

defer such problems.

·

NZ govt is paying undue attention to

economic issues but much less to political/security issues.

·

On security and politics there is a

limited amount to be done, other than increasing an awareness of the problems

US-China relations are likely to give rise to. On economic and cultural issues,

the New Zealand government should take concerted steps to plan in a coherent,

whole-of-government way for China to play a much greater role in New Zealand

trade, investment, education and tourism, and to encourage more Chinese

language and cultural skills in New Zealand.

·

Yes, it’s playing the issues quite

low-key in public, which is sensible.

·

Yes, but more effort needs to be

taken to address public perception of the relationship with China and to re-evaluate

NZ’s value to China.

·

Yes, to the extent it can. Given the

power asymmetry in the relationship New Zealand will feel it has to appear

conciliatory whenever problems arise.

·

Yes, basically. It is working quite

pro-actively in addressing potential challenges.

·

The government seems to be working

diligently to establish closer ties to China, both with the Chinese political

and business elite, as well as people-to-people, which will be useful in

dampening any tension that does flare up. These linkages could be useful in

stopping tension developing into a full-blown crisis, but due to (in no

particular order) (i) our imbalanced economic relationship, (ii) significant

political and cultural differences, and (iii) divergent security interests,

tension in the bilateral relationship seems inevitable. The government does

appear to be laying the groundwork to deal with future tensions, but is perhaps

overly accommodative towards China on economic issues to prevent tensions in

that sphere from bubbling up. This is somewhat balanced by a tougher stance on

security and human rights issues, although tension caused by NZ’s tougher

stances have mostly stayed hidden from view.

2. Do you

believe the US Government is taking appropriate steps to address sources of tension (economic, security,

ideological/political) between the US and China?

·

No, ultimately appropriate adjustments would require the US to cede

influence and accept China as an equal player in the

economic and security spheres, which does not sit well with the US view of its

global role.

·

Yes, but Washington acts with a

realist mindset that may serve to heighten tensions.

·

Tensions are inevitable between the

status quo power and the rising power. The US appears to be maintaining a

balance between holding firm to the essentials of its position in Asia and with

allies, and gradually allowing room to accommodate China’s emerging ambitions.

·

The US and China have both, in the

last 5 years, set up a super structure of dialogue tracks to smooth out these

problems.

·

The US Government recognises that there are both

cooperative and competitive aspects to the bilateral relationship with China.

At times, there seems to be disagreement between the White House, the NSC, and

the State and Defense departments as to how robust the US response should be

when tested by China.

·

The annual US-China dialogues on

security and economics and hundreds of officials-level consultations mean the

USG is aware of differences but adapts to them and contains them within the

policy that officially identifies China as a partner, not a rival or

enemy. Individual officials (CINCPAC,

cyper command) and non-government individuals are more outspoken in criticism

of China, or warning of ‘coming war’ etc.

But this is not White House or State posture.

·

No

·

US needs to engage more effectively

on economic front esp re: TPP, but also in exploring engagement with AIIB and

One Belt One Road.

·

Not enough.

·

On the whole, yes. On trade, in the

unlikely event of TPP being put into effect the next US administration should

try to get China included. It should also try and participate in AIIB. On

security, it should try and seek an agreement on the mutual accommodation of

currently defined needs in the South China Sea, and give fresh consideration to

joint initiatives on Korea and even possibly Taiwan. Of course if Donald Trump

becomes president the prospects in all these respects will be highly uncertain.

·

No. At the moment the election is

taking all attention and subsequent responses will depend on the outcome

·

No, the US government’s handling of

the relationship is largely driven by domestic [political] considerations.

·

Yes

·

The US Government recognises that

there are both cooperative and competitive aspects to the bilateral

relationship with China. At times, there seems to be disagreement between the

White House, the NSC, and the State and Defense departments as to how robust

the US response should be when tested by China. The fundamental nature of many

of the ongoing and potential problems is such that they are unlikely to be

ameliorated unless China adopts a different posture or the US decides to

concede. It should go without saying that the whole nature of US-China policy

could change considerably depending on the outcome of the US presidential

election.

·

Generally, yes. The US is working

pro-actively with engaging China’s leadership on economic, political and

security differences. Still differences over the South China Sea, for example,

could result in an accident or inadvertent crisis.

·

Bilateral tension in all of the

above spheres is constant, and likely to remain so, though the intensity

varies. The US government is managing tension with China relatively well,

pushing back on some issues and cooperating productively on others. However,

the policies of the next US administration are unknown, and the current

political climate in the US could push politicians to advocate stricter

policies against China. On the flipside, growing nationalistic sentiment within

China, sometimes encouraged by the government, could prove to be as much, if

not more of, a barrier to managing the inevitable tension in the US-China

bilateral relationship.

3.

Are there any indications that NZ’s

increasingly close security/military relationship with the US is

undermining or affecting its relations with China in any way?

·

Not yet, although this may not be the case in the future. It was

notable that China effectively fired a warning shot across the bows when it

complained about New Zealand’s recent participation in an FPDA exercise in the

South China Sea, so friction with China over the close NZ-US military

relationship cannot be ruled out. Whilst New Zealand and most other regional

states do not want to have to choose between China and the US, China may put

pressure on them to choose Beijing over Washington.

·

None that I’m aware of. NZ’s favourable response to the Arbitral

Tribunal’s ruling on the SCS artificial islands came close to raising tensions

with Beijing but it was carefully worded and did not actually name China. I’m not aware of any top-level Chinese criticism

of the Washington Declaration or other US initiatives to link with NZ, in

comparison with PRC criticism of Australia’s close links with the US and Japan.

·

Not that I know of, but it is something that China will be monitoring closely.

·

On the surface New Zealand tries

hard to appear as independent as possible, with a “no surprises” policy in

order to re-assure China of its intentions. Underneath, NZ’s relationship with USA is much deeper (given revelations

of GCSB and NSA cooperating in hacking).

China has sent messages accordingly.

·

It’s a potential concern for China,

but the level of NZ security/military relations US is not “close” enough to

significantly affect its relations with China.

·

There are occasional public comments

of a cautionary character, but no indication that China is re-thinking its

strategic defence relationship with New Zealand.

·

No evidence of this; perhaps NZ is

not viewed as threatening and certainly has demonstrated a more independent

foreign policy. There is evidence that

it helps us improve our relationships with a number of other Asian countries

who also lean towards the US.

·

No.

·

Not at this stage but this is

possible.

·

Not really as yet.

·

Not yet.

·

Not yet, no.

·

Not that I’m aware of.

·

No. China understands the

relationship NZ has with the US. They are not frightened by them.

·

Yes.

·

Not yet, although this may not be

the case in the future. It was notable that China effectively fired a warning

shot across the bows when it complained about New Zealand’s recent

participation in an FPDA exercise in the South China Sea, so friction with

China over the close NZ-US military relationship cannot be ruled out. Whilst

New Zealand and most other regional states do not want to have to choose

between China and the US, China may put pressure on them to choose Beijing over

Washington.

·

I don’t really see evidence of this.

China seems to see some benefit to itself of NZ having close security ties with

the US.

·

Not to my knowledge. NZ seems eager

to balance the increasingly close security relationship with the US by bringing

China into the fold on security issues where it can.

4.

Are there any indications that NZ’s

increasingly close economic relationship with China is undermining or affecting its relations with the US in any way?

·

None. The US and NZ are together on urging China to

comply with WTO disciplines, and to join the TPP.

·

Not that I know of

·

No. NZ’s relations with the US are

only getting stronger.

·

No, if it’s purely economic

interests and relations. Yes, when this becomes part of Washington’s overall

calculation of NZ’s value in US strategic relations with China.

·

No. Some Washington commentators

claim NZ is misty-eyed over the economic relationship but no signs this is the

‘official’ approach. There is good understanding in Washington of the reasons

why NZ and many other US friends and allies have formed close economic ties

with China.

·

That’s more or less the same

situation that every country in the Asia/Pacific is in, including the US.

·

No.

·

No.

·

No.

·

Not really.

·

Not yet, no.

·

Not that I’m aware of.

·

Only to the extent that in its

absence China is becoming more important as an economic partner than the US.

·

No.

·

No.

·

No, I don’t think so. China today is

the most important economic partner with many countries US friends and allies

in the region.

·

The US seems to understand and

respect that as an exporting nation, NZ will have close economic ties with

China. As our economic ties with China have increased dramatically, so have our

political and military ties with the US, while our economic ties with the US

have also increased, although not at the same scale or pace. The US seems to

regards NZ as a trusted partner in Asia, who can be relied upon to convey

messages to China, despite the economic relationship.

5.

Do

you see any issue(s) that are arising, or might arise, in the next 10 years

that could lead NZ to distance itself from either the US or China so as to

maintain its relationship with the other?

·

Any forcing of a choice will have to

come from either Beijing or Washington; a choice will not be made by

Wellington, and even if a choice is urged by a great and powerful friend,

Wellington will try to dodge it, as it did the Iraq invasion, and Wellington

will then emphasise other policies that will placate the demandeur.

·

As a balancing act, any shifts in

the international strategic environment will make such hedging difficult.

·

Managing relations with the two

large powers will be the single biggest challenge for New Zealand diplomatic

tradecraft in the next decade and beyond. There is no obvious issue existing or

likely to emerge in the medium term that would compel New Zealand to ‘make a

choice’.

·

Yes. It is not improbable that

should Sino-US relationships deteriorate, that there will be implicit and

explicit pressures for New Zealand to take sides.

·

The most likely issue would be a

serious escalation in the South China Sea. If China decided to play hardball in

the event of a major action, by either the US or China, they could apply

significant pressure on NZ to distance ourselves from the US. Likewise, the US,

while likely to understand our economic interests in such a scenario, would

likely apply pressure on us to take a tougher position than we may be

comfortable with. Both sides would wield considerable leverage over NZ in the

event of a major incident or escalation of tension in the South China Sea.

·

The formal policy is that there is,

and won’t be, any contradiction, contra to Rob Ayson’s views. Any forcing of a choice will have to come

from either Beijing or Washington; a choice will not be made by Wellington, and

even if a choice is urged by a great and powerful friend, Wellington will try

to dodge it, as it did the Iraq invasion, and Wellington will then emphasise

other policies that will placate the demandeur.

· The two relationships will be a factor in NZ policymaking in many areas, but I think the most likely scenario would be for NZ to make a decision onthe merits of a particular situation that would have the incidental effect of enhancing or detracting from one or the other of the relationships.

·

NZ needs both China and the USA and

therefore needs to be more engaged with both.

It hedges on a closer economic relationship with China, and as a

“strategic partner” in the Pacific region, while cooperating with the USA

militarily at levels not see for 30 years. As a balancing act, any shifts in

the international strategic environment will make such hedging difficult.

·

How hard will US continue to push

for its Pivot to Asia; Directions of further development in regional economic

institutions; China’s interests and investment in economic relations with NZ

further expand.

·

Managing relations with the two

large powers will be the single biggest challenge for New Zealand diplomatic

tradecraft in the next decade and beyond. There is no obvious issue existing or

likely to emerge in the medium term that would compel New Zealand to ‘make a

choice’.

·

If either side disturbs the current

order (including international laws and norms) in some substantive way then NZ

should be prepared to note that bilaterally.

·

Yes. It is not improbable that

should Sino-US relationships deteriorate, that there will be implicit and

explicit pressures for New Zealand to take sides.

·

If China goes onto the military

offensive in Southeast Asia (unlikely) NZ could distance itself from China.

·

Possibly – but will depend primarily

on how China chooses to exercise its power in the region and in NZ which affect

NZ interests.

·

Three issues

o

Political chaos in China

o

Economic crisis in China

o

Isolationism in the US

·

Yes. In a crisis one or other side

might insist on New Zealand taking a less impartial position than it has

striven to do to date.

·

Obviously, the possibility exists in

either direction, but NZ seems to be attempting (sensibly) to balance the

relationship.

·

NZ will want to continue to maintain

a balance between the two.

·

Yes.

·

I think New Zealand will find it

increasingly hard to avoid making some sort of choice as the previously

parallel tracks of its politico-military and economic interests begin to

converge.

·

NZ relations with China could be

negatively affected if China-US tensions escalate particularly in the South and

East China Seas.

·

The most likely issue would be a

serious escalation in the South China Sea. If China decided to play hardball in

the event of a major action, by either the US or China, they could apply

significant pressure on NZ to distance ourselves from the US. Likewise, the US,

while likely to understand our economic interests in such a scenario, would

likely apply pressure on us to take a tougher position than we may be

comfortable with. Both sides would wield considerable leverage over NZ in the

event of a major incident or escalation of tension in the South China Sea.

6.

Has New Zealand welcomed the US ‘Pivot to Asia’

(rebalance)? If so – why?

·

Quietly, yes, but avoided

emphasising it. Many NZers are sceptical of it and of the US, so the NZG find

no political capital in publicising it. The US warming is welcome because it

validates NZ policy and assists the NZDF, that is, it serves NZ interests. But

NZ has no wish to exacerbate US-PRC tensions by overtly taking one side or the

other. So policy is an artful and pragmatic muddle. This must be frustrating to

those who want clarity and focus.

·

Yes because we perceive the US as a

stabilising force in the region.

·

Yes, the Defense White Paper sees

the strengthening of US-NZ relations between their armed forces as enhancing

NZ’s regional security.

·

“Welcome” is perhaps not a right

description of NZ’s position and interests on this.

·

Yes. A strong and committed US

presence in the Asia-Pacific is essential to maintenance of a stable region

environment that is conducive to economic progress.

·

Yes, New Zealand is on record as being

in support of the Pivot. Minister Coleman’s statements around the Washington

Declaration signing refer. It would be the majority view of states in the

Asia/Pacific that maintenance of a US presence in the region is a stabilising

factor. Most lean to the US, although

expect to also have a solid relationship with the US. The Pivot should not be viewed as a

containment strategy (which it clearly is not – granted that China’s official

statements dispute this), but it is a shaping and hedging strategy. And while China is a big part of the pivot,

we do not see it as the sole security question in the Asia-Pacific. The pivot

is a range of diplomatic and military initiatives (and hopefully TPP will one

day add an economic dimension) that covers a range of security contingencies,

from natural disasters to the current dire situation on the Korean Peninsula.

·

Yes, New Zealand has welcomed the

rebalance. The reason is clear: to ensure regional peace and stability. The US

is a force for stability in the Asia-Pacific

·

The NZ Government has

welcomed the US ‘pivot’ but many NZ observers are concerned about the

‘containment of China’ simplifications of the ‘pivot’.

·

It seems so, mostly because a

stronger US economic + military presence can serve to balance a rising China

and the uncertainties that presents.

·

Yes, mainly for security reasons.

·

New Zealand has responded cautiously

to the rebalancing policy, or rather tried to avoid responding explicitly. Why?

Simply because its attitude has been determined by its interest in sustaining

good relations and even improving relations with Washington while doing the

same with China.

·

Yes, it makes sense for the US to be

deeply involved diplomatically, economically, socially, militarily, but as

primus inter pares rather than ‘leader’.

·

Yes. A more engaged US in Asia

strengthens security and economic conditions and therefore benefits NZ.

·

Yes, in order to maintain a

strategic balance in the region.

·

Yes, because it has undoubtedly

enabled and accelerated the rebuilding of the New Zealand-US military

relationship as Washington has sought Wellington’s participation and support.

·

Yes, it has. NZ sees the value of

the US seeking to provide countries in the region, particularly in Southeast

Asia, Korea, and Japan at least some counterbalance to China’s increasing

assertiveness in the South and East Chia Seas and continuing support for North

Korea.

·

Yes, because (i) the Government sees

a role for NZ as a facilitator of the US-China relationship, and (ii) it should

lead to increased US engagement in both Asia and the Pacific, including New

Zealand. It has also spurred the TPP, although the agreement may be torpedoed

by the US Congress.

7.

Should New Zealand try to play a role as an

intermediary in US-China relations?

·

Absolutely not the concept of NZ as an ‘honest broker’ is the product of delusions of grandeur.

·

Yes, but only if invited jointly by

both parties. Very difficult to see where a unilateral initiative to seek such

a role would be welcomed or could be helpful. What is important is to have

access to senior political/policy leaders and the ability to talk to both

sides.

·

Absolutely not: it is likely to get

crushed! Not only would trying to play such a role almost certainly be

unsuccessful, it would most likely cause difficulties in New Zealand’s relations

with both countries.

·

It really can’t play a major

intermediary role, although it can serve to carry messages between the two of them

from time to time.

·

New Zealand can certainly play a

constructive role between the two countries. In the process we can potentially

have an outsize influence on both, although we need to walk a very fine line

and choose our battles carefully to avoid being caught in the middle or being

on the wrong side of issues.

·

If asked by either side, yes. But

other than working productively with each in turn, e.g. in the UNSC or APEC or

RCEP or ADMM+ or ARF, NZ should not put its and up. It would produce risks and costs that would

far outweigh the benefits (if any) ‘blessed be the peacemaker’ but dismissed as

naïve is the failed idealist, e.g. NZ initiative to bring Israel and PA to the

table.

·

No. While NZ can share perspectives

and views, neither China nor Washington need a third party intermediary.

·

There is potential for NZ to have that

influence.

·

Yes, but only if invited jointly by

both parties. Very difficult to see where a unilateral initiative to seek such

a role would be welcomed or could be helpful. What is important is to have

access to senior political/policy leaders and the ability to talk to both

sides.

·

Only if these countries ask for it,

which they are not. What would we be

offering? No country currently plays a

role like that.

·

No.

·

No – at least not formally.

·

Only to a very limited extent.

·

Only in very modest ways in very

particular circumstances. It is too small a player to have any except a

peripheral influence on the relationship.

·

No.

·

No. We should focus on our interests

and we are at best a marginal player in terms of the US & China.

·

Yes.

8.

Is

there a risk to NZ from the unequal nature of the NZ-China relationship? (i.e the difference in the two nation’s economic size

and scale)

·

Yes, the asymmetry of power in the

relationship is a reality and a risk. We cannot wish it away. But there are way

to ‘manage’ the situation. New Zealand should do its best to support an active

role for the US in the region. If the US is not actively serving as a balancer

to Chinese power, China will seek to maximise its influence over small and

medium size states. This has been the historical experience of the region when

China was strong.

·

Yes. Elsewhere China has shown

itself quite ready to use its political influence to secure its economic goals,

and vice versa. There is no reason to suppose New Zealand will be exempt from

this.

·

Yes. New Zealand will effectively be

forced to accept things which are not necessarily in its own national interests.

·

Yes – China holds considerable

leverage over NZ due to its size. NZ has so far proven adept at managing this

and being treated more or less as equals, although NZ should be prepared for

China to occasionally throw its weight around.

·

Yes. Unexpected adverse trade policies could damage NZ severely but NZ

policies are insignificant to China.

·

Of course, it makes NZ vulnerable to pressure from China. This is no different from the pressure we have been subjected to in the past by other major economic partners such as the UK, France, the EC, the US and Australia.

·

China can turn on or off trade in

response to anything it may be upset with, or at least to signal

dissatisfaction.

·

Yes, same as with the NZ-US

relations.

·

Significant scale differences are a

standard feature in all New Zealand’s major relationships. Managing those

disparities so as not to become overly dependent is at the core of NZ

statecraft. The China relationship is no different, we are not at Beijing’s

beck and call.

·

The risk is one of over dependence

on a single market – much like the situation we were in with regards to

dependency on the UK market. When the

market disappears or hits troubled waters, a vulnerable economy needs the

alternatives. That said, we have done

extremely well out of the Chinese market, which helped us ride out the GFC

without really much impact.

·

Yes – hence the importance of broadening

the bilateral relationship

·

Absolutely. China is building

significant leverage.

·

NZ should learn to deal with

individual provinces as well as China as a whole.

·

No.

·

Yes definitely. Making the

relationship more complicated to manage, and harder for NZ to have impact in

China.

·

Yes.

·

Of course, there is always that risk

particularly on the economic front as NZ becomes more active in trading and

investing with China, but NZ so far has sown itself to be quite shrewd in

maintaining its independence.

9.

Should

NZ take a public stance on territorial/sovereignty disputes between China and

its neighbours over the South and East China Seas?

·

NZ should stand firmly on

international law but avoid identifying international law-breakers, which would

make NZ part of the problem.

·

Not unless NZ interests are directly involved, or there is an egregious and clear cut violation of international law.

·

No. NZ’s public stance is not to

take a position – only opposing any action that undermines peace and trust, and

to support recourse through international dispute settlement

processes/institutions or direct negotiation.

·

No, and NZ’s current position is

fine. There is no solid basis upon which NZ can form a more substantive stance.

Benefits in taking such a stance are not entirely clear.

·

The government’s public comments

have been carefully nuanced, with appropriate emphasis on the importance of the

norms of international law but without taking sides over particular disputes.

·

New Zealand has made public

statements on this. See statements by

Ministers McCully and Brownlee. Such

statements are often carefully worded, but we are in support of UNCLOS and a

peaceful resolution of this situation.

·

New Zealand already has. It should

continue to do so.

·

Not beyond reaffirming NZ’s

commitment to the rule of law globally.

·

Probably not necessary.

·

Yes.

·

No, other than by urging all parties

to seek a peaceful resolution of the disputes concerned, as it has done. From a

realist perspective there would be no benefit in taking a more explicit public

stance, and in any case the rights and wrongs of the disputes are complicated.

·

No.

·

We should continue to stick to an

established posture: we look to international rules and expect all countries to

abide by them.

·

Yes.

·

Whilst it should continue to refrain

from taking positions on sovereignty claims of the disputants, it should adopt

a firmer position on the need for the parties concerned to not only respect

international law, but to actually adhere to it. New Zealand cannot say it

supports a rules-based international system and then fail to condemn states

which flout the rules (e.g. China and the Permanent Court of Arbitration

ruling).

·

Yes NZ should communicate its

concerns about wanting to see the rule of law maintaining and the avoidance of

the use of forces to resolve territorial disputes. OF course, NZ should not

take sides on who owns what.

·

Yes – NZ’s interests are clearly

served by large countries, such as China, adhering to international law and

international norms. We of course must be careful not to significantly

jeopardise our economic interests, but nonetheless, on security issues

affecting the stability of the wider Asia-Pacific, and impacting US-China

relations, we should make our commitment to international law and the pacific

settlement of disputes publically known, and stand up for those fundamental

values and interests.

10. Is

there anything else you would like to add regarding New Zealand’s relationship with China, and/or its

relationship with the United States, and the potential national security

implications for New Zealand of this triangle?

· While we academics, and policy analysts, and

military officers, would like more decisiveness, courage, and moral backbone

from the NZG, presumably in favour of the US and its democratic neo-liberal

ideals, a nuanced examination reveals the wisdom of its current understated and

ill-defined policies. Large majorities of the NZ public are sceptical of the US

(and even more are sceptical of China) so keeping control of the policy

narrative by avoiding energising these minorities is prudent NZG policy. The

visit by the US Navy ship in November will test the NZG’s skill in narrative

management.

· As well as the risks, there are opportunities stemming from the greater attention and consideration we get from two major powers both seeking to guild their influence in our region.

·

NZ and USA

share common values, laws and language and a longer history of joint

involvement. Our value systems are

fundamentally linked. With China, the relationship is more recent and developing and ultimately

will become stronger too. Continued

engagement through thick and thin is the key.

· After the special and enduring ties with Australia,

there are the two paramount bilateral relationships with New Zealand. They are

many-hued and multi-faceted. While complex they can be managed without damage

to New Zealand’s core national interests.

· We are a Strategic Partner of the United States and

have an important partnership with China. These relationships are different,

qualitatively, and both are important to manage. In the event of a major crisis, depending on

who is at fault, NZ would be in a position to make representations to either

side. It should also be noted that NZ’s strategic dilemma cannot be simply

boiled down to US and China, which is frequently the way the question is

framed. When issues of international

law emerge within ARF or EAS this is not just a situation of the US v China.

Most of Asia (Australia, Japan and much of ASEAN) also look closely at our

statements. There is also the principle that New Zealand regards as critical,

which is the importance of international laws and norms – as a small state it

is integral to our foreign policy independence. So issues like the South China

Sea are not simply about which large power we are “siding with”. The stakes are far higher than that. In the end, and New Zealand’s official

statements to date deal with this, it is about thinking carefully about both

values and in fact the majority of our global connections (including notably

Australia, our most important relationship). (The situation in Crimea/Ukraine also refers.). On our 5 Eyes

partnerships, the majority of states in our region have intelligence agencies,

and, one can assume, intelligence relationships of their own. The world is awash with such

arrangements. I think that is well

understood that NZ will have its own arrangements in this space, particularly

amongst states who possess very large intelligence gathering apparatuses of

their own.

· Handling ‘this triangle’ is likely to be the most

challenging diplomatic issue NZ has ever faced.

· NZ is a small nation with no geopolitical interests

in getting caught between the two superpowers.

· The New Zealand Government would do well to develop

contingency plans for (a) its burgeoning relations with China (see point 4

above), (b) a sudden deterioration in triangular relations.

· There don’t have to be security implications if it’s

properly handled.

· I think New Zealand is too small and unimportant to

be part of any triangular relationship with China and the US though I know what

the question means. It might be better to think of an Australia-China-US

triangle and how this affects New Zealand. It will be difficult for New Zealand

to continue to adhere to a softer policy towards China, as the line across the

Tasman hardens, without becoming very out of step with our principal ally.

·

Trying to maintain an equidistant

relationship with the PRC and US when NZ is trade dependent on the PRC and

security dependent on the US is akin to straddling a barbed wire fence while

standing on ice blocks. The strategic competition between the US and PRC in the

Asia-Pacific region is the ice that undermines the balancing act and at some

point a hard choice will have to be made to go one way or the other. The best

way to resolve the dilemma is to act as an intermediary between the two powers

while recognising the respective dependence on each.

·

NZ is well

positioned to improve our relationships with both countries, particularly in

areas where they are underperforming – for instance economically with the US,

and politically/militarily with China. NZ can also play a constructive role as

a go-between in the US-China relationship, thereby allowing us to “punch above

our weight” with both countries and on the international stage. Nonetheless,

this is a difficult and potentially treacherous role to play, and we must

manage it very carefully, as the potential consequences of failure are high. In

terms of national security, the main threat to NZ from the US-China

relationship seems to come from a destabilisation of the wider region, rather

than from a direct threat to NZ’s territorial integrity or political

sovereignty.

[1] Reuben Steff & Francesca Dodd-Parr, ‘Examining the Immanent Dilemma of Small States in the Asia-Pacific: The Strategic Triangle between New Zealand, the US and China’, Pacific Review (January 2018, available online. Free e-print access: http://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/TypQnQ7ukRRtqQkAmUKB/full)

Comments

Post a Comment